The year was 1939 and storm clouds were brewing over Europe. With Germany becoming increasingly aggressive, Great Britain knew she would soon need a steady supply of pilots, navigators, and bombers – three crew types that required considerable time and money to train. This need would bring together two of the greatest aeronautical minds of the time and would spur the creation of the most advanced flight training device ever built.

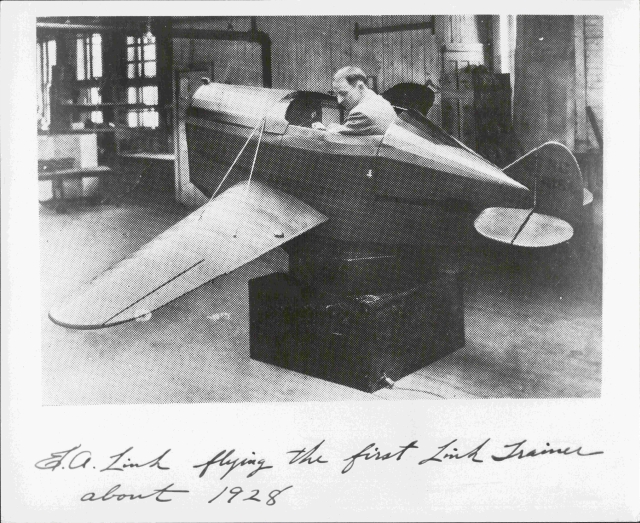

Edwin A. Link Jr. had been building flight simulators since the 1920s. Born in 1904, and living in Binghamton since 1910, with occasional sojourns to California and Illinois, Link finished his first flight simulator in 1928 in the basement of his father’s factory, the Link Piano and Organ Company. Later, when discussing why the first trainer needed a wingspan of exactly 9’2”, Link replied, “Well, that’s the biggest wingspan we could have and still get the trainer into the freight elevator in the piano factory”. He used parts he found in the factory, creating suction using old organ bellows, to build a device that resembled a small airplane, capable of banking, pitching, and yawing. His original idea was to build a ground training device that would reduce the expense of flight training, thus making flying more accessible.[1]

The Link Trainer, colloquially known as the “Blue Box” after the color most were painted, would initially receive a frosty reception, with Link resorting to selling it to amusement parks as a novelty ride.[14] The winds would soon change Link’s fortunes.

In 1934, the Army Air Corps, having recently begun flying the mail after an airline scandal, suffered a series of fatal airmail crashes. These accidents were attributed in part to the pilots’ inexperience flying in poor visibility. As a result, Link received a contract for his simulators from the United States government to teach their airmail pilots flying by reference to instruments. His simulators were incredibly effective, and Link Aviation, his Binghamton- based company, grew to be extremely successful.[1]

In the late 1930s, with war imminent, Great Britain approached Ed Link with a request that he design a trainer to more quickly and easily teach celestial navigation to Royal Air Force crews. Link was intrigued, and though he himself was a very capable pilot, when it came to celestial navigation he decided he needed to consult the very best.

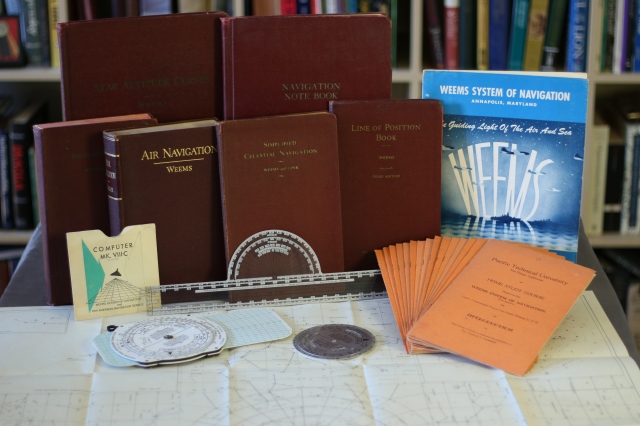

Philip Van Horn Weems was born in 1889 on a farm in Montgomery County, Tennessee, the fourth of eight children; seven boys and a girl. He was an orphan at 12, but his siblings refused to be split up, instead remaining to work the farm and pursuing their education. Weems, bright, athletic, and driven, secured an appointment to the United States Naval Academy, graduating in 1912.[12] Over the course of his naval career he would define navigation for an entire generation of pilots; some of the techniques and equipment he developed are still in use today. In 1928 he and his wife Margaret founded the Weems System of Navigation, a school offering courses and equipment in aerial and nautical navigation. He wrote several books; the most famous, “Air Navigation”, won a gold medal from the Aero Club of France when it was published in 1931, the first of many honors the text would receive. Weems would go on to publish three subsequent editions as technology and aircraft evolved.

Retiring from the Navy in 1933, Weems relocated his school from Coronado, California to Annapolis, Maryland. He would teach his navigational techniques to some of the most famous names in aeronautical history, including Charles Lindbergh, Amy Johnson, and Admiral Richard E. Byrd (a former Naval Academy classmate of Weems).[2][3] With the United States’ entrance into World War II, Weems would return to active duty with the Navy, serving in the Atlantic as a convoy commodore.[3]

In 1938, Link traveled to Annapolis to learn celestial navigation as a student in one of Weems’ courses, and the two men became fast friends. Weems mentioned to Link that if Link could “do for navigation what he had done for instrument flying it would be a great aid.”[4] In March, 1939 Weems traveled to Binghamton to visit with Link and collaborate on a book with the aim of demonstrating to “the thousands of new navigators who will take up celestial navigation within the next five years that it is not black magic.”[5] The book, “Simplified Celestial Navigation”, was published in January 1940 and sold through Weems’ school.

While collaborating on “Simplified Celestial Navigation” Weems and Link were also working on what would become the Celestial Navigation Trainer. In development for over two years, the first CNT was delivered to Great Britain in 1941. The immense value of the CNT was recognized immediately, both in Britain and the US. Against today’s computer-driven, full motion flight simulators, the CNT seems archaic, but in 1941 it was a marvel of design.

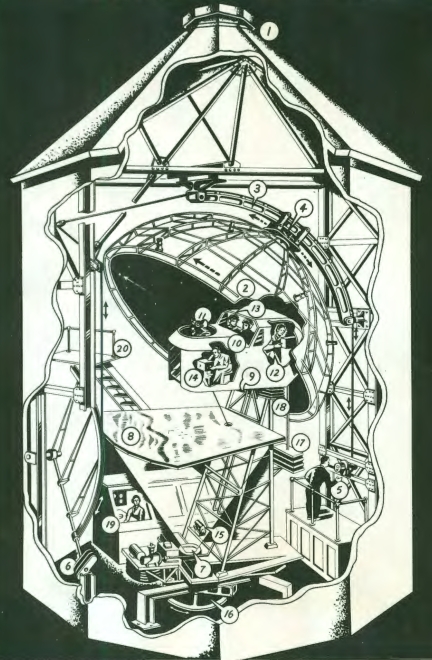

The Celestial Navigation Trainer was housed in an octagonal silo 45’ tall. A larger version of Link’s basic “Blue Box” trainer was mounted inside the silo about halfway up with room not only for the pilot but also a navigator, bombardier, and radio operator.

Like the “Blue Box”, the “airplane” in the CNT could pitch, roll, and yaw in keeping with the inputs from the pilot (10). From the navigator’s position at the front of the trainer (11), a student could use a sextant to take sights of stars mounted on a dome (2), simulating the night sky of the Northern hemisphere. The dome was constructed out of chicken wire, stretched over a frame. Collimated lights were mounted throughout the dome simulating hundreds of stars, both those used for navigation and others to make the “sky” seem as real as possible. Through an intricate set of gears functioning as an advanced clock (4), the dome would rotate based on changes in the “airplane’s” longitude as well as move on a rail (3) to simulate a change in latitude.[6]

A screen was installed below the trainer with moving images of terrain projected on it (8), allowing bombardiers (14) to practice using a bombing sight. With over 210,000 square miles of terrain to choose from, instructors could select missions to be accurately flown over American, Japanese, or German areas.[7] Typical training missions started with a crew being given a flight plan and target. The navigator practiced his art to direct the pilot to the target, when the crew began their bombing run. The navigator then switched places with the bombardier, who could practice with a working bombsight.[8] A point of light would shine on the projection below to let the crew know where their “bombs” hit.[6]

The brains of the CNT were located at the instructor’s station in a separate room below the trainer (19). From there an instructor could manipulate virtually all aspects of the training experience. Wind could be added, and smoke could be used to simulate fog obscuring the stars, terrain, or both. The progress of the flight was be drawn by a device in the instructor’s station as well, allowing for detailed analysis of training missions afterwards. Aside from the obvious benefits of being able to train multiple crewmembers much more cheaply, safely, and faster than in actual airplanes, the CNT was an early exercise in what is today called Crew Resource Management. It allowed many different crew types, who previously had trained individually, to learn to work together as a functioning, capable crew.[6]

Between 1941 and 1945 hundreds of CNTs would be built, and after 1944 many would be staffed by WAVES (Women Accepted for Voluntary Emergency Service). These women, upon completion of the Navy’s navigation training course, would serve as instructors training thousands of airmen.[9]

So many CNTs were built that the Binghamton Times wrote in 1944 that the reason it was “tough to get chicken wire to keep your hens out of the neighbor’s victory garden” was because the “lowly bale of chicken wire has gone to war” in the construction of CNT celestial domes. They estimated that by 1944 3,388,000 square feet of chicken wire had already been used to help navigator trainees find their way to Germany in Link CNTs.[10]

As flight simulators became more computerized, Link would move into other ventures, although his company would continue to produce high quality flight trainers. Link’s passion for underwater exploration lead him to several important inventions in that field, including submersibles and rescue equipment, as well as historical salvage missions in Israel, Greece, and the Caribbean.[1] In 1959 Link and his wife Marion visited Jamaica as part of a National Geographic expedition to explore and map the city of Port Royal, which had sunk in an earthquake on June 7, 1692. For help with the underwater mapping, he called in his old friend P.V.H. Weems.[11]

After World War II ended Weems retired from the Navy again, now with the rank of Captain. He would be recalled to active duty one more time, in July, 1961 at 71 years old, this time to develop and teach a means of navigating in space.[12] He passed away on June 2, 1979 at the age of 90.[3] Edwin Link passed away two years later on September 7, 1981. He was 77.[1]

Today none of the CNTs survive, although if you look hard enough you can find evidence of them. A few miles north of the small town of McCook, Nebraska are the ruins of the McCook Army Air Base. While it was home to over 15,000 servicemen and women from 1943-1945, today it’s a series of dilapidated hangers and overgrown pavement.[13] Look closely though, and you can see four octagonal outlines in the dirt, the foundations of the silos that once housed Edwin Link’s and P.V.H. Weems’s technological marvel, the Celestial Navigation Trainer.

Sources:

[1] Van Hoek, Susan and Marion Clayton Link. From Sky to Sea: A Story of Edwin A. Link. Flagstaff: Best Publishing Company, 2003. Print.

[2] Sparkes, Boyden. “Teaching “Lindy” Navigation.” Popular Science August 1928: 53-54, 108. Print.

[3] “P.V.H. Weems, Helped Develop Space Navigation.” The Washington Post 4 June 1979: C8. Print.

[4] Van Dyck, Louis K. “Bomber Crews Now Rehearse On ‘Ground’.” The Gettysburg Times 9 December 1942: 6. Print.

[5] Weems, P.V.H., and E.A. Link Jr. Simplified Celestial Navigation. Annapolis: Weems System of Navigation, 1940. Print.

[6] Link, Edwin A. Celestial Navigation Trainer. Edwin A. Link, assignee. Patent 2,364,539. 5 Dec. 1944. Print.

[7] Cawley, Thomas R. “Link Celestial Navigation Trainer Puts Crew Of Bomber Through Battle Paces Inside ‘Silo’.” The Binghamton Press 17 November 1943: 8. Print.

[8] Scott Jr., Robert L. “Bombing Tokyo From a Silo.” Popular Science Apr. 1944: 57-58, 198. Print.

[9] “WAVES Study For Jobs On Link Program.” Naval Aviation News 1 August 1944: 16. Print.

[10] “Chicken Wire Goes to War to Play Stellar Role in Guiding Our Pilots Straight to Targets” The Binghamton Press 12 June 1944: 13. Print.

[11] Link, Marion Clayton. “Exploring the Drowned City of Port Royal.” National Geographic February 1960: 151-183. Print.

[12] Anson, Cheryl. “At 73 He’s Gone Off Into Orbit.” The Baltimore Sun 18 November 1962. 16-17. Print.

[13] Nebraska Historical Marker, McCook Army Air Base.

[14]Kelly, Lloyd B. as told to Robert B. Parke. The Pilot Maker. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1970. Print.

Only wanna comment that you have a very decent website , I love the style it actually stands out.

LikeLike

A fascinating read. Thanks.

LikeLike

I’m researching and learning marine celestial navigation and am having a difficult time finding information on how the original mathematics of how the sight reduction tables were calculated. Lots of information on how to use the tables but no information on the mathematics behind the construction of the tables. Also looking on the history of this. Any information would be greatly appreciated.

LikeLike

Great article! I’m a great nephew of PVH Weems and I just happened to see this article. This was nothing I knew of PVH so just in case the rest of the family didn’t know, I sent the link on. Good move on my part because PVH’s granddaughter who lives in Annapolis didn’t know this and was delighted to read about it. She said she went to Jamaica on that Port Royal trip. That was written up in the February, 1960 National Geographic. And my link to Link was in 1987, I volunteered at the Southern Museum of Flight in Birmingham, AL and they had a Link Trainer that didn’t work. I worked on it and got it going, actually got to “fly” it once.

LikeLike

What a wonderful and incredible piece of “forgotten history” and an excellent capture of this incredible time and the incredible characters involved. I have interest in the watches connected with early aviation and have perhaps the best collection of Weems and Lindbergh vintage historical watches. I am in the process of writing up some of the articles on flightbirds.net about Weems and all the characters of this incredible chapter of aviation history and better chronicling this golden period of aviation re the timepieces used. I have been chasing the pre Weems training materials of Weems (Especially the one on the aero chronometer) in case it yields some extra unknown details and perhaps anyone with knowledge regarding a relationship between Weems and Henry Hughes and Son in London and or Harry Nash from San Diego Jessops fame who may have edited Weems first pre Longines Weems Second-setting watches. Once again thank you for the wonderful history lesson.

LikeLiked by 1 person